Last Saturday I had the privilege of attending a Groundwork/Horsemanship training clinic with Kip Fladland, of LaRiata Ranch near Griswold, Iowa. It was the first horse training clinic I have ever been to. I’ve been around natural horsemanship training my whole life, having grown up next door to Kevin Wescott (a Tom Dorrance and Ray Hunt style of trainer), who helped me get started training horses when I was a kid. But that was twenty years ago, and I’m needing to expand my groundwork techniques, and am always eager to learn more things I should be doing with my horses.

Last Saturday I had the privilege of attending a Groundwork/Horsemanship training clinic with Kip Fladland, of LaRiata Ranch near Griswold, Iowa. It was the first horse training clinic I have ever been to. I’ve been around natural horsemanship training my whole life, having grown up next door to Kevin Wescott (a Tom Dorrance and Ray Hunt style of trainer), who helped me get started training horses when I was a kid. But that was twenty years ago, and I’m needing to expand my groundwork techniques, and am always eager to learn more things I should be doing with my horses.

So I trailered Penny to La Riata Ranch, and we did groundwork all morning, and riding all afternoon. Kip is a friend and student of Buck Brannaman; he rides western, outfitted like a California-style vaquero with the big horn saddle, snaffle bit, mecate, chaps, flat-crowned hat and wool vest. His wife Missy is a dressage rider, so you see all types of horses at their place. Kip used a big chestnut Quarter Horse mare for the morning’s work, then rode a black Warmblood mare for the afternoon.

Penny and I joined a group of eleven other pairs of horses and handlers, with a few spectators auditing the clinic. Penny adjusted well to the newness of the indoor arena (it had ground up something for footing that was mostly gray but had little specks of color in it, and she kept sniffing it like “what in the world is this?”) and the close proximity of the other horses, and after a few snorts and looks around, she settled in well and stood respectfully awaiting a command.

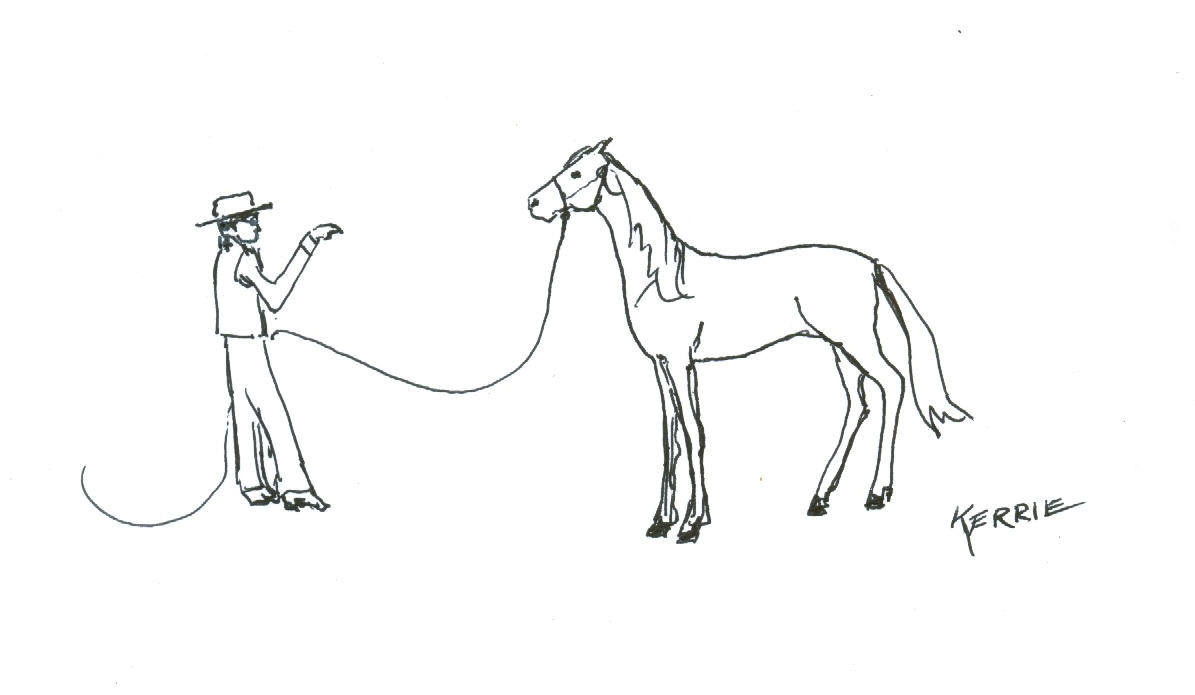

The first excercise we were assigned was to direct our horse in a circle around us, at a good walk—“with life in their feet”, Kip would say. Penny required tapping with my longe whip, as she wanted to meander slowly and stop if I didn’t keep after her. Kip said, “Kerrie, too much slack in your rope. If she spooks or acts up, she could be on top of you, or half-way across the arena, before you get her stopped.” And another time, “Kerrie, try not to have to continually tap her. Send her in a circle, don’t constantly touch her with your stick.” (Kip was really good at remembering every rider’s name—I don’t think he messed up a name on all twelve of us!) So Penny wasn’t super proficient at walking with life in a twelve foot circle…but hey, I’ve never even lunged this mare before, so I thought she did wonderfully. We did this, switching directions now and then, for a dizzying half hour.

The next thing we worked on was asking the horse to back. Kip demonstrated with his mare, on a loose lead rope, motioning in the air above and in front of his face, for the mare to step back, and she did. He would motion and she would step back, and he would motion again and repeat until she was all the way to the end of his 15 foot rope, where she’d stand, waiting for direction. Then he’d ask her to come back to him, and would pet her face and let her stand.

He told us, with less responsive horses, to “put some action in the rope”, meaning an up and down flipping motion, to get the horse to take a step back. He said to pause and release pressure every time the horse moved a front foot. Some horses required more action, which he called “sending a coil down the rope”, and looked more like a sideways jerk of the rope that snapped under the horse’s chin and got their attention and they’d immediately step back. Then when he would ask with a more gentle up and down motion, the horse would step back more responsively. Then he’d ask the horse to walk back up and be petted and rewarded with a release of pressure. He said if the horse wouldn’t lead back to you, you might have to step off to the side of the center line and ask the horse to walk back up to you.

Penny didn’t do so well with this backing up method, as my poly lead rope was too short and very soft and didn’t have a lot of effect on her (I really had to shake it to get any motion to translate into the headstall of the halter to where she would even feel it or notice.) But I didn’t bring this to Kip’s attention, because I figured the fault was in my lead rope, not in my horse.

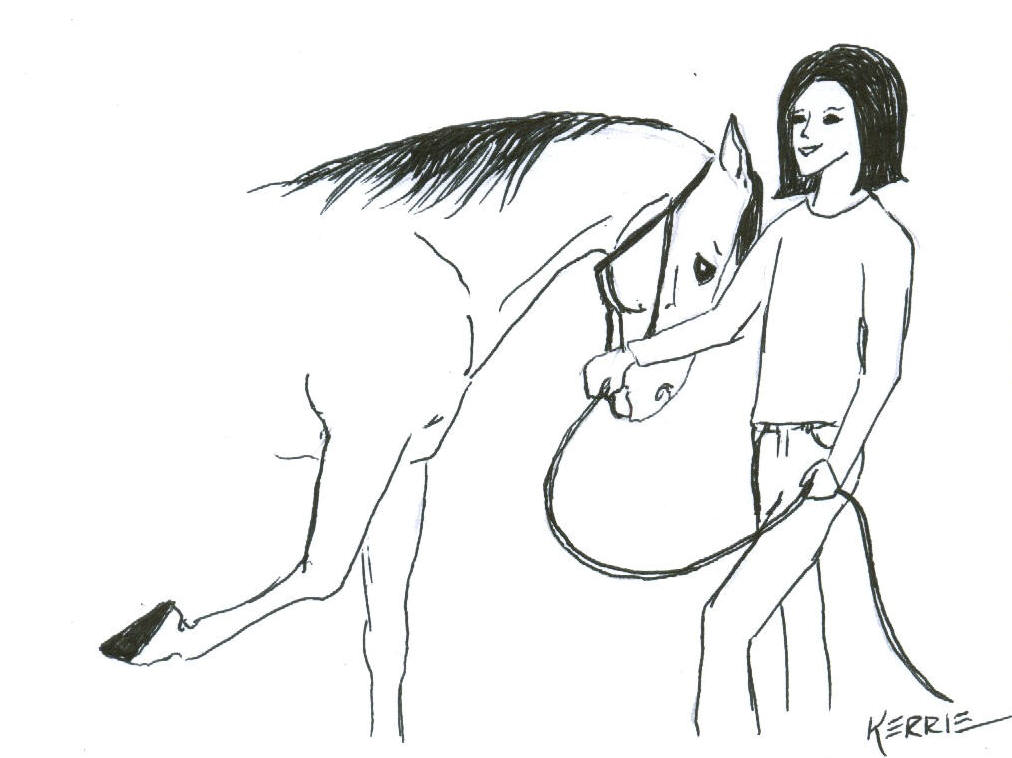

The second method of backing that we practiced was to stand beside the horse’s head, facing backwards. He said to put our hand, thumb down, elbow up beside the horse’s face, and grip the knot of the halter (not the knot of the lead rope). Then ask the horse to walk backwards briskly by pressing backwards with a side to side motion of the knot, creating a rubbing pressure with the noseband against the horse’s nose. He said their backing up would mimic the trot, and we should work on it to be straight backwards, smooth, and with a “soft feel”, which he explained was evident in the horse’s head and face—elevated poll (head shouldn’t be lower than the withers), tucked chin, and no bracing against the pressure of your hand on the halter knot. He said the reason for having your thumb down and elbow up between you and the horse’s head was for safety—“a horse’s head is a fifty pound hammer on the end of a five foot handle”, and it’s easier to put a cast on your arm than a cast on your skull. The more you practice this, the lighter pressure will be required to get the horse to back up, and the horse will be more conscious of you and what you are asking of it.

He would pause in between exercises to go over other things that can be worked on to perfection, such as putting the halter on. He said when you approach a horse to halter it, you should go prepared and have it ready in your hands. Go to the horse’s left side, get your right arm over the horse’s neck, and use pressure to lower their head to wither-height or lower. (Release pressure every time the horse lowers its head, even if it’s just a little, as a reward for doing the right thing.) If the horse evades by turning it’s head to the left, away from you, use the thumb of your right hand to press under their ear, at the indention above their jowl, to encourage them to keep their head towards you and the halter as you put it on. He said to practice it until the horse is soft and easy to handle. The horse will become eager to seek the halter with its nose and be so much better to halter.

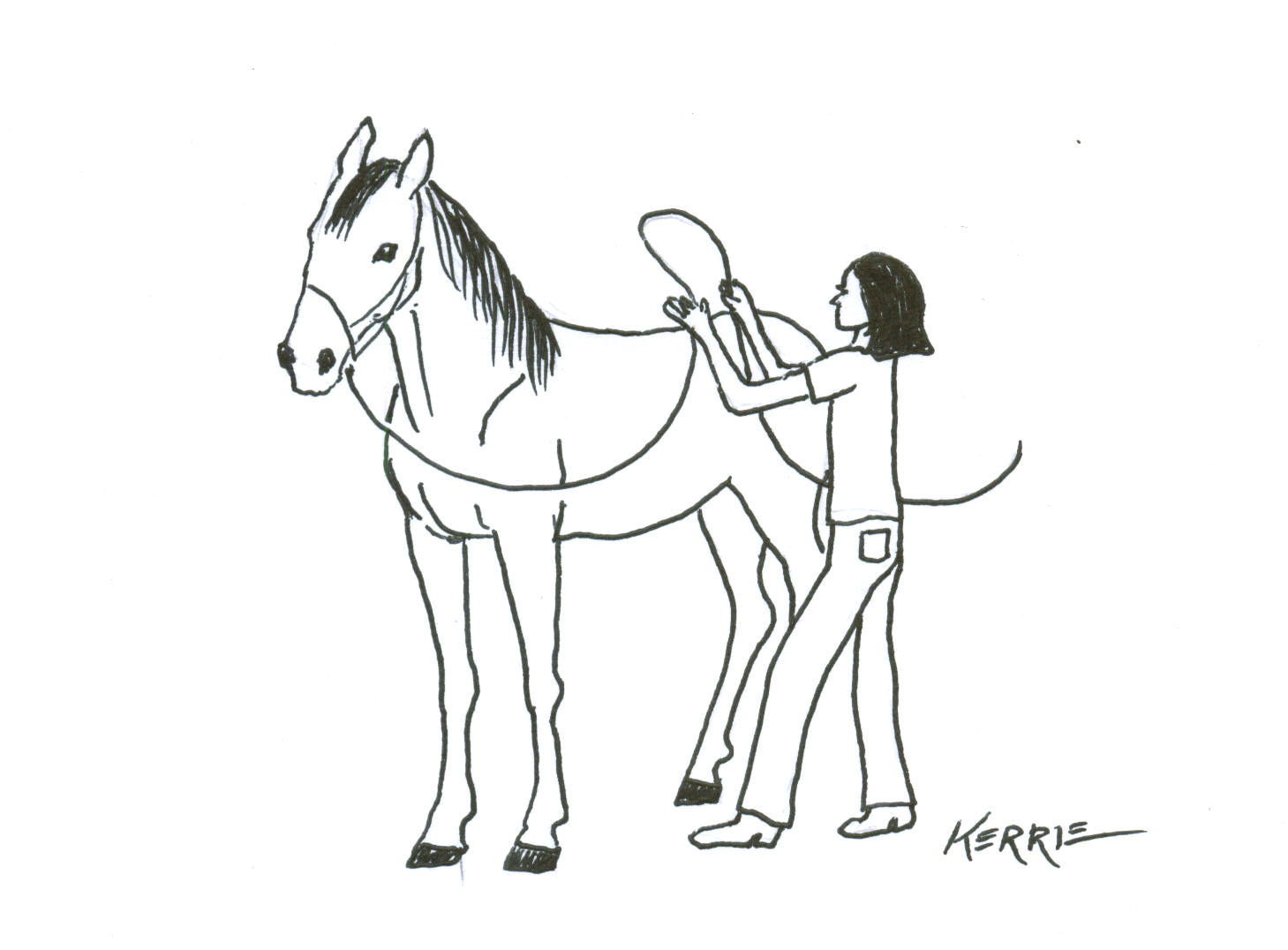

Kip also said when you’re working with a young horse or flighty horse, to use the halter rope to get the horse used to being ridden, before you get on. He demonstrated by tossing a u-shaped loop of his lead rope up onto the horse’s back, pulling it off, throwing it again repeatedly. He said not to flip the whole end over the horse’s back, but just a loop of it. He said don’t lay it up there, throw it. Your goal is to get the horse used to motion around him and the feel of something on its back, and to develop a trust of the handler to not give him more than he can handle, but create situations that might spook a horse during riding, and get the horse used to it so nothing the rider does is scary. He also used a flag at the end of his training stick to whip in the air and make weird sounds, touch the horse all over and get it so it doesn’t spook at things touching him.

Another exercise we were presented with was to ask the horse to disengage the hindquarters in a turn, and bend and soften its head and neck and come to a stop with its head around near us and a soft feel (poll elevated, ears level, not braced against the pull of the lead rope, etc.) We did this by standing on the horse’s left side, facing the horse’s tail, our left hand up on the cantle of the saddle (or horse’s back, if it wasn’t saddled) and the lead rope in front of our belly and held snugly against our right hip bone by our right hand. The horse should turn its hindquarters away from you as you advance and walk towards the cantle of the saddle in a tight circle. The horse’s left hind should be reaching far in (to the horse’s right) to carry its hindquarters to the right. When the horse stops is feet and is standing with its head bent around to the left towards you, check to see that the horse’s poll is as high as it’s withers, its ears are even (one is not lowered pointing to the ground—if so, ask for it to straighten by a little more pressure on the rope), and there is no bracing against the rope or pull, so the horse is submitting to the pressure with a soft feel, then release all pressure and let the horse relax as a reward.

Penny was surprisingly very good at this, which makes me wonder again if she was worked with quite a bit when she was young (I have no idea what training she went through before I got her). One thing Kip said was, if the horse just bends his neck but doesn’t disengage with his hindquarters and move in a circle, use your left hand to bump him in the side where your leg would bump him if you were in the saddle, right behind the stirrup, in front of the back cinch. Use a bumping motion to get him to give and move to the right with his hindquarters, stepping far in with his hind leg closest to you. Until he stops his feet again, and stands with his head bent around with a “soft feel” and the correct position. Then switch sides and repeat everything.

After that we worked on changing directions half way around the circle. Then Kip showed us something to work for that most of us couldn’t accomplish, at least not with the fluidity that he and his horse demonstrated. He said, “I am going to start out at this end of the arena and simply walk straight to the other end of the arena.” He sent his horse around in front of him to the left, and as the stirup of the horse passed him, he switched hands on the lead rope, threw up his left hand in front of the horse and sent the horse back to the right. Again, as the horse’s stirrup passed in front of him, he switched hands on the lead rope, threw up his right hand in front of the horse, and sent the horse back to the left, all continuing to walk slowly to the other end of the arena, where he turned and executed the sideways figure eight all the way back to the spot where he had begun. It looked so easy, watching. But the horse was very in-tune to every movement, and very quick to respond. When I tried it with Penny, Kip said, “Kerrie, you’re waiting too long to switch and ask her to turn and go back.” So I was letting Penny get almost behind me before I sent her back around the other way. Also, Penny wanted to cut in close to me as I walked, rather than circle and keep a distance. I had a lunge whip, but a flag would have been helpful to keep her in a good arc around me rather than fall in and cut across the circle. So that’s definitely something to work on and perfect.

Kip talked about leading a horse with a soft cotton rope around the front foot. He said it’s good to get your horse to yield his feet, and to be able to place the horse’s foot wherever you want it. He talked about getting on a horse, how to properly step into the stirrup and avoid jabbing the horse’s side with the toe of your boot when you get on. He said grab a hunk of mane to help get on, don’t pull on the saddle.

He also talked about when you ask your horse to move into a circle or arc around you, the first motion the horse should take is to move away from you and give you space. As in, move sideways away from you first, then around the circle. This is something that would be really good to work on with young horses. He said there’s nothing wrong with the horse coming to be close to you when you are letting it rest or after its done the right thing. But when you are telling it to move, or sending it in a circle, it should not walk over the top of you, or step in towards you to begin its circle. Its first step should be away. To correct that, you might have to exaggerate your sending movements, if the horse tends to fall in towards you. Or use your flag, lead rope, or lunge whip to move it back away from you. It is better to be aggressive the first time it happens and teach the horse to not do it, than to let the horse to develop a bad habit of not caring where it steps and perhaps stepping on top of you.

We also worked on a very simple concept of leading and stopping. Kip said there should be about three feet of lead rope between the horse’s head and your hand. The horse should be following at your same pace or rate of speed, and if you look to the side, you should not see horse. In other words, the horse should not be ahead of your shoulder at any time. When you stop, the horse should stop with you, in its tracks, slightly behind you, without bumping into you. If it doesn’t, correct it by motioning it back sharply with your hands up high eye-level with the horse, and use the lead rope to give a jerk backwards if the horse doesn’t get the message. Your goal is for the horse to watch and mirror your movements whenever you are walking. This is a great thing to practice often. Kip said the horse should lead from both sides, right and left. If the horse lags on the rope, or doesn’t lead well, use a whip or flag in your other hand, to switch around on the horse’s side behind you to encourage it to step up and follow at the right speed. For young colts, this might take a lot of practice. Penny was perfect at it.

Most of what we worked on was designed to gain control of the horse’s hindquarters. He said if you can control the hindquarters, the front feet won’t be a problem. One catch phrase he repeated often was “Observe, remember, and compare.” For instance, if his horse did something just short of perfect, he would see it and notice it and remember it for next time and work to get it better and compare what the horse did. Then he said when you get it perfect, stop. Don’t keep repeating something that was good—reward the horse for doing it right by quitting and letting the horse rest.

We also were to constantly work on keeping the horse’s focus. If Penny glanced at the open door of the arena as we passed it, Kip would say,”Now if she looks at that door, you pull her head and correct her for that.” He was very conscious of each move of every horse, and would correct a lot of wrong ones. For some people, he would take the lead rope and work the horse himself, and while he seemed very forceful for wrong behaviors, it often ended with him being very soft and getting the right result. He talked about people who lose their temper with a horse, and he said not to do that. The horse doesn’t keep score and doesn’t understand if you’re still mad at him for something he did half an hour ago. He said when there’s a problem, correct it, and then get over it.

It was a very good experience for both Penny and I, and I would really like to be able to go to his next clinic in a month, and take a different horse. All of our horses would benefit from what Kip teaches, and I would love to be able to send Bluebird to him to train. I talked to Kip after the clinic, and we discussed training Bluebird, but he is filled up until spring, and I think now that I’m equipped with some groundwork ideas, I can work with her myself and see how she behaves. A very reassuring thing that Kip said during the clinic is that if your horse can complete these groundwork exercises and you are able to then move to the saddle and repeat them all on horseback, you don’t have to worry about the horse bucking or running off with you. You control the horse’s feet and everything else falls into place.

(Since I was riding in the clinic and trying to be a good student, I wasn’t able to take any photos. These drawings and descriptions are my own interpretation of the training that took place, and any error is not to be taken as a reflection on Kip Fladland’s training expertise, but rather of my own understanding and drawing ability or lack thereof.)